A honeynet infrastructure to battle SMS scammers

Lia Gold-Garfinkel

Oct 10, 2024

Smishing (or SMS phishing) has resulted in millions of people around the world losing their hard-earned money through mobile money scam transactions. Bernard Odartei Lamptey from Carnegie Mellon University Africa's Upanzi Network hopes to combat this by collecting more data about this cyber crime in order to develop ways that users can protect themselves. To do this, Lamptey along with Assane Gueye, Edith Luhanga, Mohammed Seidu, and Karen Sowon have created an inexpensive honeynet infrastructure, to intentionally draw in smishing messages from scammers so that they can analyze the data.

Lamptey explains that these fraudulent mobile money transactions follow a specific pattern, where the hacker first crafts a transaction message that is sent to the user. These messages are often designed to appear as if they are coming from legitimate mobile money services offered by companies like MTN and Airtel. If the user is unaware of these types of scams, they respond to the scammer. The attacker then calls the user, claiming that the user was sent money, which needs to be returned. This results in the user transferring their own money straight to the attacker.

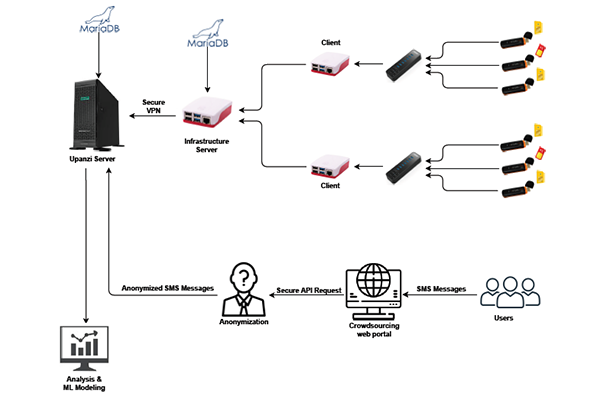

Lamptey explains that the honeynet infrastructure they developed is both flexible and cost-effective, allowing for further expansion of their dataset. This is accomplished with a Raspberry Pi, USB multipliers, GSM modems and SIM cards. With this setup, one Raspberry Pi is able to host seven modems at once; that is the infrastructure is able to mimic seven mobile phones at once in order to trap hackers. This also allows the infrastructure to be centralized, in that they have one device to collect all of their data. Lamptey explains that this kind of large-scale data collection has been difficult in the past due to the sheer amount of devices needed to collect this information, making the process both expensive and disorganized.

Currently, Lamptey's dataset includes smishing messages collected from users in Rwanda, Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, and Uganda. Users' personal information is extracted prior to placing their messages into the dataset. Lamptey hopes to expand this project as he mentions a current limitation is that they had a relatively small pool of data to initially analyze. One prediction the team has is that Rwanda may not have as many smishing messages as they thought. This, however, does not leave out the possibility that transaction-based scams in Rwanda are more so focused on calls or voice messages instead of SMS messages.

Source: Bernard Odartei Lamptey

Lamptey intends for researchers from more universities and countries to contribute to the dataset. Lamptey’s team currently works with two collaborators. One includes researchers from Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (UCAD) in Senegal who are working on setting up the infrastructure in their lab, equipping it with SIM cards from different MNOs, collecting smishing messages, analyzing these messages and testing the resilience, ease of set up and use of the infrastructure. The other is with an NGO based in Rwanda called GiveDirectly.

"During one of our conferences here in Rwanda, we were showcasing our project and GiveDirectly walked up to us and said their beneficiaries are being targeted," Lamptey explains. Lamptey is hoping to eventually have more collaborators like GiveDirectly so his research team can gather data from different organizations and provide advice to protect their stakeholders from smishing attacks.

Lamptey goes on to explain that a second phase of this smishing project will be to develop a machine learning model that would be the base for a messaging app for Android and IOS users. Users can then use this messaging app for all of their SMS messages, and it would be able to tag and warn users of incoming smishing messages. This phase of the project will have a number of obstacles, the main one being mobile money transaction messages in English instead of the commonly spoken local dialect in a particular country. During the research, we observed that mobile money transaction messages are worded in English. However, one of the main objectives the team set out to achieve was to have a machine learning algorithm that can analyze messages worded in the local dialect.

"If we're able to build a model for that, maybe we can have other investors in other countries like Uganda pick it up and train the model in their own local languages," Lamptey says.

Lamptey's message and work is bringing about increased cybersecurity awareness for African countries, which will surely make the online world we live in a safer place.

Learn more by reading "Demo: A Low-Cost Honeynet Infrastructure For Smishing Data Collection," published in COMPASS '24: Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGCAS/SIGCHI Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies.